JournalismPakistan.com | Published February 28, 2025 at 02:01 pm | Dr. Nauman Niaz (TI)

Join our WhatsApp channel

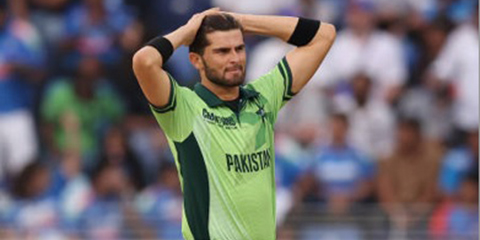

It is difficult to say why Aaqib Javed’s press conference even needed to happen. Difficult because the manifestation itself, like so much of Pakistan cricket, carried with it, the absurdity. Aaqib has always lived and spoken with the straightforward, undisguised brusqueness of a man who has seen too much and says too little, stood there curiously distanced, unconnected from himself, a man disillusioned from his candor, stuttering his way through a script that was not entirely his, nor entirely believable.

There is always something faintly tragic about watching a man wrestle with the words placed in his mouth, as though he has become a character in someone else’s drama, a repository for someone else’s incoherence. This was not a press conference, not in any conventional sense. It was closer to a public autopsy, except the body on the table was Pakistan’s selection philosophy, or whatever survives in its name, and the man asked to conduct the autopsy was neither willing nor qualified.

Pakistan cricket’s selection dysfunction is not new. Its pathology is so old now that it no longer surprises, it only exhausts. But rarely has it been exposed so openly, in the full light of day, with a man like Aaqib, who once represented a sort of fast-bowling rebellion, now reduced to its messenger. This was not the shambling incompetence of one man on trial, nor the failure of one group of selectors, but something far deeper, the absence of any philosophical scaffolding within which selections could be made with intent or perspicuity.

Aaqib’s insistence that this was the best available squad was not so much a defense as it was a resignation, a submission not just to the failures of this moment, but to the accumulated failures of ages. The thing about Pakistan squads is they have always been capable of individual brilliance. That is not the point. The point is how rarely those individuals have been assembled into something greater than themselves, and how often Pakistan mistakes the existence of stars for the presence of a constellation.

Act of Picking of Names

Selection is not the act of picking names. It is the far rarer art of constructing a team from conflicting talents, of balancing restlessness with stability, of pairing the proven with the possible. This is what the great selectors understand, that the essence of selection is not in the names themselves, but in the spaces between them, the connections and contrasts that create something larger than its parts. It is an art that Pakistan’s selectors, over generations, have never even aspired to.

Aaqib himself was once a symbol of defiance, the fast bowler from the other side, neither Wasim Akram nor Waqar Younis, but still there, still running in. And yet here he was, speaking not from that spirit of rebellion, but from the hollowed-out space of a man asked to defend the indefensible. There was a sadness to it, not just for Aaqib, but for the system that made him, broke him, and now asked him to explain itself.

If there was a revelation, it was not in what Aaqib said but in what he could not bring himself to say that Pakistan cricket, for all its illimitable talent, has long since lost any sense of what it is trying to build. There is no philosophy, no intellectual framework, no attempt to understand what a Pakistan cricket team could or should be in this age. There are only quirks, urges,, impulses, grudges and favours, all basted together into something that sometimes looks like a squad, but more often resembles an uneasy truce between competing factions.

There is no cricket culture more adept at mistaking potential for performance, or hype for substance, than Pakistan’s. In the lead-up to the ICC Champions Trophy 2025, what surfaced was not so much a squad as a symptom, a vivid, chaotic expression of the deep, unmoving dysfunction that defines selection in Pakistan. Each name in the squad was less an argument for itself than a reflection of the forces that put it there, the politics, the nostalgia, the desperation, the fear of what might happen if someone else was chosen instead.

Aaqib Javed is Not the Man We Know

That Aaqib, a man whose career lived in the long shadows of Wasim and Waqar, and whose post-playing life has been spent in the comfortable purgatory of the Lahore Qalandars and Dubai academies could look at this mess and call it ‘inexperience’ is not just wrong, it is insulting. This is not inexperience. It is institutional amnesia, the wilful forgetting of every lesson this cricket has tried to edify Pakistan over the past thirty years. It is not just dishonesty. It is defacement, destruction, and the deliberate expurgation of history to protect the fragile egos of selectors and administrators who cannot tell the difference between insight and instinct.

This was not a squad built on principle, or even on a plan. It was an accident, the product of inertia and the compromises that keep men in jobs they do not deserve. The result was inevitable. A lone specialist spinner in conditions that cried out for many. One specialist opener summoned not because of vision, nor strategy, nor any sense of coherence, but because the alternatives had exhausted themselves. He had been cast aside before, not for his faults but for theirs, punished less for his failings than for the unforgivable sin of seeing the system for what it was and daring to say so aloud.

Fakhar Zaman’s absence from the tours of Zimbabwe, Australia, and South Africa was not selection, it was retribution. He had scored four centuries in One Day Internationals between 2023 and 2024, a lonely figure on the shifting deck, the only player capable of rupturing a game’s trajectory, the only batter who understood that in modern cricket, the impact was not a statistical afterthought but the very currency of relevance. He was, for a time, the closest thing Pakistan had to a white-ball game-changer, which, in this system, was never an argument in his favor.

It was only when Saim Ayub, Pakistan’s newest sensation, twisted his ankle in a way that mirrored so many of his predecessors’ careers, that the selectors relented. They called Fakhar back, but not with open arms, rather with the hesitant reluctance of men forced to confront their limitations. His recall was not a philosophical correction, but an administrative necessity, a response to the randomness of fate rather than the clarity of thought. Why did they want only one specialist opener? One solitary, fragile thread from which they hung the weight of a tournament and a philosophy they never truly possessed. And why, for his understudy, did they choose a player yet to debut in One Day Internationals, a player whose few T20 appearances, scattered and nervous, left no imprint save for their futility?

Usman Khan had been catapulted into this narrative not through performance, but through that distinct Pakistani selection alchemy, where the potential is imagined, not proven; where a few Pakistan Super League innings substitute for method, and where a vacancy matters far more than a vision. His technique was a work in regress, his fluency a myth spun from fleeting domestic bursts, and his fitness the kind that comes from playing cricket not as a profession, but a pastime. He was not so much a player as he was a placeholder, a name to fill the void, an offering to fate.

Even the selectors, in their heart of hearts, knew they had erred. That much became clear the moment Fakhar Zaman was ruled out, when, faced with the issue of actually sending Usman Khan to open, they recoiled. They reached instead for Imam-ul-Haq, a man they had discarded not long before. Imam, whose offense had been dual, his strike rate, too modest for their imagined future, and his loyalty, compromised by the belief that he had been too loose-lipped about the dressing room’s inner fractures.

Intellectual Dishonesty

That Imam, despite all this, was still preferable to their chosen backup was not just an indictment of Usman Khan. It was a confession, that the selectors, for all their plans and processes, had none. Imam’s recall was not an endorsement, but an admission that survival, not coherence, was the governing principle. It was not just the absence of insight. That would have been forgivable, even familiar. What unfolded instead was a selection process untethered from both logic and imagination, a cart moving forward not because it knew where to go, but because stopping was no longer an option. This was planning without purpose, decisions without destinations, and selection reduced to the blind ticking of boxes in a system too afraid to ask itself what kind of cricket it even wanted to play.

The signs were there, long before the ICC Champions Trophy 2025 arrived. Imam-ul-Haq was cast aside, discarded not only for his strike rate but for speaking too freely, of allowing the dressing room’s whispered discontent to leak into the public air. But where, in the space Imam vacated, was the foresight to invest in Shan Masood? Here was a Test captain, a batsman whose List A record wasn’t just respectable, it was brilliant in comparison to his peers. He existed, was available and capable, but never considered, because to plan is to understand the conditions of the future, and these selectors lived only in the confusions of the present.

Saud Shakeel, technically sound and temperamentally sculpted for the middle overs, was similarly left to drift, a player of rare pedigree, trained by the hard-handed spinners of domestic cricket, left unutilized for reasons that were neither tactical nor philosophical, but simply absent. His exclusion was not a decision, it was an oversight, which is how most selections, and non-selections, happen in Pakistan cricket. And when the time arrived, he was included in the squad, a knee-jerk reaction, as usual.

Shadab Khan’s story was, in itself, a parable of modern Pakistan cricket, a player torn between identities, trying to be a top-order hitter, a defensive spinner, a captain, a brand. The result was inevitable — a player not developed but deformed by his versatility. His leg-spin had long since lost its venom, a casualty of this existential crisis, exposed brutally at the World Cup. Yet he lingered — not because his role was clear, but because his absence would have exposed the selectors’ confusion.

It was not only the individuals left out that spoke of this fundamental disorder, it was those summoned. Mohammad Wasim Jr., a bowler whose numbers in the middle overs stood among the best, not just in wickets, but in economy, found himself bypassed for Aamer Jamal. The latter, a better Test all-rounder, was never fully suited to the format, but that was irrelevant. This was not selection, it was improvisation. And then, in true Pakistani fashion, came the late-stage parachuting of Rana Fahim Ashraf, a player absent from all prior plans, dropped from the central contract list itself, yet somehow pulled into the squad as if selection was not a process, but a scavenger hunt for warm bodies.

The contracts themselves told their tale — on October 27, 2024, the selectors had issued them, the supposed backbone of future planning. And yet, by the time the squad was named, five players not awarded contracts were in the squad. No List A cricket had been played in the interim. No performances had justified the shift. Fakhar Zaman, discarded in October, reappeared like a ghost they could no longer deny. Rana Fahim Ashraf, similarly excluded, was summoned as though absence itself had been mistaken for form.

Among the chosen were Irfan Khan Niazi, the bright young batsman flaunted as a future investment, until, of course, he was excluded from the squad itself. Shadab Khan, who had been given a contract, was dropped. Mohammad Hasnain, uncontracted, was somehow essential. Tayyab Tahir floated in limbo, neither part of the central plans nor discarded. What was exposed was not merely confusion, it was the system’s inability to differentiate between a plan and an accident.

The problem, as always, was not the names themselves, Faisal Akram, Qasim Akram, Arafat Minhas, Jahandad Khan, Sufiyan Muqeem, they were neither the disease nor the cure. They were symptoms, fragments in a mosaic of improvisation that Pakistan’s selectors have long mistaken for a plan. The issue was not just that they were chosen; it was the absence of a reason for their choosing.

Senseless Selections

In a world where selection should be an expression of cricketing philosophy, a reflection of how a team understands itself, Pakistan's selectors approached the tours of Zimbabwe, Australia, and South Africa with all the clarity of a man shopping in a fog. Every tour, every match, became its isolated episode, unlinked to the next, unanchored to any larger scheme. Other teams, from Australia to South Africa, used these matches as laboratories, places to test hypotheses, refine combinations, and settle questions. Pakistan, however, used them like confessionals, opportunities to absolve past selection transgressions and indulgences by offering new faces as penitence.

Zaman Khan and Akif Javed were not only overlooked, they were reminders of what happens when selection is guided not by vision but by superstition. Both were bowlers with skills Pakistan might have built around, Zaman, a specialist in death-over chaos, capable of thriving in conditions of maximum pressure; Akif, with his raw left-arm promise, a natural counterbalance to Pakistan’s right-arm-heavy attack. They were omitted not because they didn’t fit, but because no one bothered to define what the team should be.

The greatest failure was not in the selection itself but in the absence of a philosophical framework to justify it. Squads were picked not to prepare for the Champions Trophy but to perform on tour because in Pakistan cricket, the future has always been too distant to matter. Every selection is about now, this match, this press conference, this minor victory to cover a larger defeat. To plan is to risk accountability. To improvise is to always have an excuse.

What resulted was a fundamental misunderstanding of what these matches were for. Australia and South Africa knew they understood that winning a preparatory series matters only insofar as it prepares you for the tournament that follows. Pakistan, though, played for the scorecards, for the press releases, for the fleeting calm that comes with a 2-1 result. They played as if the Champions Trophy was a mythic horizon, forever out of reach, rather than an event that would arrive, indifferent to their readiness.

This is the philosophical core of Pakistan’s selection madness — an inability to think of time as continuous. Each tour, each squad, and each match exists in isolation, disconnected from the last, unlinked to the next. There is no arc, no continuity, no story. Just a series of desperate attempts to stay afloat, to survive the next press conference, and to give the illusion that selection is a process rather than a plea.

And so, Pakistan cricket approached yet another ICC tournament with a squad formed not by logic or necessity, but by a long sequence of avoidance, forgetfulness, and the occasional burst of guilt. It was not a team, it was an archaeological site, layered with the fossils of old failures and the artifacts of fleeting hopes, where every name is less a choice and more a confession. Irony, in Pakistan cricket, is never incidental. It is structural, the very marrow of its existence. That two players, freshly anointed with the honor of national caps, found themselves unworthy of selection by their domestic teams was not just surprising, it was inevitable. In a system without philosophical coherence, where selection is neither the culmination of process nor the reward for sustained excellence, but instead an evanescent act of whim and circumstance, this contradiction is the natural order of things.

To be chosen for Pakistan is not always to be validated. Sometimes it is to be exiled from the logic of the game itself. It is to be placed on a stage where you are simultaneously celebrated as the nation’s future and quietly disowned by the very system that produced you. It is to become, at once, indispensable and unwanted.

In a rational world, the national team would represent the peak of a seamless, meritocratic ladder, the end of a story written through performances that demanded elevation. But Pakistan cricket has never adopted rationality. It is a world that exists in fragments, where selectors see players as inventions of the moment, divorced from the contexts that shaped them. A player is called up not because his domestic record compels it, but because a selection committee, desperate for a name that feels new, reaches into the fog and pulls him out. And the domestic system, with its own politics and prejudices, shrugs, having already moved on.

That these players could be summoned by the national team, then discarded by their domestic sides, is not an oversight. It is the perfect expression of Pakistan cricket’s fatal flaw: a culture that treats selection not as the fulfilment of a journey, but as a random act of alchemy, a process by which ordinary cricketers are transmuted into international players, without anyone ever being clear why, or for how long.

This is the paradox at the heart of the system: selection without faith, elevation without investment, rejection without consequence. And so these players, who should be walking the domestic fields with the quiet pride of men chosen by their country, instead become symbols of the absurdity of it all. To wear the national shirt is to step into a void, where the past no longer matters, the future is unwritten, and the present exists only as an accident.

Pakistan selectors lived in fog

Pakistan’s selectors have always lived in this fog, trapped between fear of consequence and the illusion of control. What they desire most is plausible deniability. They do not choose players; they choose alibis. They do not build teams; they assemble contingencies. In this system, selection is not about identifying talent, it is about managing the narrative for when failure inevitably arrives.

What emerged ahead of the Champions Trophy was not a squad, but a palimpsest of abandoned ideas, discarded philosophies, and half-remembered instincts. It was a team evolved not from cricketing vision, but from the sheer gravitational pull of past mistakes, a team assembled not to win, but to survive its own announcement.

Not Aaqib Javed, not Azhar Ali, not even the most articulate apologists like Asad Shafiq could summon the words to justify the logic that birthed this squad, a squad that was less a team and more a riddle, a koan, a circular argument without resolution. How could a side tasked with defending Pakistan’s title in the ICC Champions Trophy 2025 be entrusted to the hands of Khushdil Shah, Rana Fahim Ashraf, and Usman Khan, men whose very inclusions seemed like whispered confessions of defeat rather than proclamations of intent?

It was a team where selection was not the product of design, but the consequence of exhaustion, the selectors retreating, step by step, from every ideal they once professed. One spinner, one opener, and a hundred unsaid doubts carried into the tournament like heirlooms of a family that had long forgotten their value but still feared their absence.

And what of Irfan Niazi? What sin did he commit to warrant omission in favor of Tayyab Tahir? In Pakistan cricket, absence is not explained, it is endured. Players disappear not because they failed, but because the system forgot how to see them. Selection here is not just about form, it is about memory, about who lingers in the imagination of those with power and who fades into the static noise of the domestic season.

The question was never why this squad was chosen, the question was why anyone thought there would be answers in the first place. To some, it was never truly the team selectors had intended to choose, it was a team shaped by the slow, grinding weight of inevitability. Selections in Pakistan cricket are never final, only provisional, constantly subject to forces both seen and unseen. What emerged was not a squad born from conviction, but one dragged into existence by circumstance, each alteration a reluctant concession to reality.

It is a uniquely Pakistani ritual, selection as an act of resistance, a defensive manoeuvre rather than an affirmative choice. A player is dropped not because his time is done, but because someone’s patience has frayed. A player is recalled not because he has thrived, but because the alternatives have collapsed. The final team is less a coherent whole than a palimpsest, layer upon layer of compromises, corrections and concessions, each decision haunted by the ghosts of those that came before. There is no end to the act of selection in Pakistan, only the temporary pause between arguments. The team you see today is not the team they wanted, nor the team they believed in, it is merely the team they could no longer avoid.

Worse Still

Worse still, the PCB’s management, a hierarchy as transient as the teams they assemble, seemed gripped not by the urgency of repairing a fractured side, but by the allure of steel and concrete. They spoke with pride of modernizing stadiums, of transforming tired stands into glittering arenas as if it was the walls and seats, not the men who stood within them, that would write history.

There is an almost poetic futility to it, refurbishing the stage while the actors forget their lines, polishing the grounds for a theatre without plot. To anyone watching closely, these stadiums no longer felt like venues for sport, but monuments in anticipation of decline, tombstones in waiting. In a few years from now, they may stand taller than the team itself, immovable structures commemorating the fleeting, fragile lives of the cricketers who once filled them with fleeting, fragile hope. In Pakistan cricket, the past is always present, even when dressed in new concrete.

Dr. Nauman Niaz is the Sports Editor at JournalismPakistan.com. He is a civil award winner (Tamagha-i-Imtiaz) in Sports Broadcasting and Journalism and a regular cricket correspondent, covering 54 tours and three ICC World Cups. He has written over 3500 articles, authored 14 books, and is the official historian of Pakistan cricket (Fluctuating Fortunes IV Volumes – 2005). His signature show, Game On Hai, has received the highest ratings and acclaim.

March 15, 2025: Explore the dynamic relationship between athletes and sports journalists, examining the challenges, ethical dilemmas, and mutual benefits that shape the sports media landscape.

March 08, 2025: An in-depth analysis of Pakistan cricket's descent into chaos under Aaqib Javed's leadership, examining the controversial selection decisions, political interference, and systemic failures that undermined the national team ahead of the ICC Champions Trophy 2025.

March 02, 2025: An unsparing analysis of Pakistan's Champions Trophy 2025 squad selection reveals not merely inexperience but a systemic rot of patronage networks, political expedience, and intellectual bankruptcy within Pakistan's cricket governance, continuing a tragic history of selection failures.

March 01, 2025: Pakistan cricket's selection paradox: a system where players like Babar Azam thrive despite, not because of, the process. This analysis reveals how positional shifts, political decisions, and philosophical failures continue to undermine a team capable of brilliance but hamstrung by a selection committee that mistakes chaos for strategy.

February 26, 2025: Shaheen Shah Afridi’s rise was a spectacle of raw, untamed talent. But Pakistan’s cricketing establishment failed him, leading to a career plagued by injuries and mismanagement. Can he reclaim his dominance, or is his best past him? Read the full story.

February 26, 2025: Explore the extraordinary legacy of Major Dhyan Chand, India's hockey wizard who redefined the sport, won three Olympic golds, and inspired generations with his unmatched brilliance.

February 24, 2025: An incisive analysis of Pakistan cricket's systemic failures, examining how bureaucratic inertia, self-serving former players and resistance to modernization have eroded the nation's cricketing excellence despite abundant talent.

February 21, 2025: Delve into the complex challenges facing Pakistan cricket as it grapples with outdated systems, political interference, and resistance to modernization. Dr. Nauman Niaz reveals how the transition from passion-driven success to bureaucratic inefficiency has left Pakistan's cricket legacy hanging in the balance.

April 11, 2025 Sindhi journalist AD Shar was brutally murdered in Khairpur, Sindh. His body was found dumped on Handiyari Link Road. PFUJ has declared a three-day mourning period and demanded justice.

April 10, 2025 The Azad Jammu and Kashmir government has filed a case against The Daily Jammu & Kashmir and its staff for alleged fake news, drawing condemnation from PFUJ and IFJ, who demand immediate withdrawal of the FIR and an end to media repression in Pakistan.

April 08, 2025 Journalist Arzoo Kazmi alleges that Pakistan's state agencies, including the FIA, have blocked her CNIC, passport, and bank account while threatening her. She calls it a direct attack on journalism.

April 07, 2025 The Islamabad High Court has directed IG Islamabad to produce journalist Ahmad Noorani’s missing brothers, as the Ministry of Defence denies custody. SIM activity was traced in Bahawalpur, and investigations into their suspected abduction continue.

April 07, 2025 Journalist and Raftar founder Farhan Mallick has been granted bail by a Karachi court in a case concerning anti-state content aired on his YouTube channel. He still faces separate charges related to an alleged illegal call center and data theft.