JournalismPakistan.com | Published March 01, 2025 at 07:21 pm | Dr. Nauman Niaz (TI)

Join our WhatsApp channel

This is how Pakistan cricket operates, not through layered succession plans or philosophies built on understanding conditions and combinations, but through cycles of rejection and resurrection. They do not plan for crises; they are the crisis, perpetually surprised by their circumstances. Usman Khan was never meant to play. He was a name on paper, a product of selection’s need for illusion, the illusion that there was a plan, the illusion that this was deliberate, the illusion that someone, somewhere, was in control.

There is a unique cruelty in Pakistan cricket, not just to its players, but to its ideas. No sooner is a strategy announced than it is betrayed by its own architects. Strike rates become irrelevant when there are no openers left; leaks become irrelevant when the dressing room is already a colander. Every player is both indispensable and disposable, every decision both intentional and accidental. Imam Ul Haq’s recall, Usman Khan’s redundancy, and Fakhar Zaman’s injury, are not stories in themselves. They are the latest verses in the unending limerick of Pakistan cricket, where selection is less about choosing players and more about managing regrets.

This is how Pakistan teams are made. Not from the gentle evolution of ideas, or the careful balancing of form and potential, but from the sediment of past errors and the hurried improvisations they necessitate. Selection is rarely about talent or balance. It is about survival, for players, for selectors, for administrators clinging to the illusion of control in a system designed to defy it. Fakhar’s return was neither redemption nor vindication. It was simply Pakistan’s way, the talent they cannot replace, the player they cannot love, the future they cannot plan for. His presence in the squad, like so many before him, was both necessary and accidental, a reminder that Pakistan cricket does not build teams, it stumbles into them.

This is, and has always been, the tragedy of Pakistan cricket, that its players have thrived not because of the system, but in perpetual defiance of it. Its most luminescent teams, its brief moments of brilliance, were all acts of survival, survival not against opposition, but against the machinery that selected them. Selection in Pakistan has never been an act of design, but of accident, of fortune, of who was left standing after the latest purge or factional compromise.

The very notion of philosophy, the most basic of foundations for any sporting team, was not abandoned here because it never existed to begin with. What replaced it was something older, deeper in the national psyche, hope. The hope that talent, raw and unpolished, might pull off the impossible, might stretch itself far enough to cover the cracks of its neglect. Occasionally, it did. But no system, no team, can live off miracles forever, significantly in modern times of science, tools, performance enhancement, improvisation, and accuracy.

And now, as the world leans further into systems, into process and method and science, Pakistan clings stubbornly to the idea that genius will somehow endure. Modern cricket has absorbed analytics and biomechanics, mental conditioning and skill refinement, until the team itself becomes the sum of its parts. Pakistan, however, stands alone, resistant to these intrusions, unwilling to reconcile with the idea that brilliance alone is no longer enough. It is not just science it resists, it is the idea of cricket as something planned, something constructed, rather than something destined. And in that resistance, the future keeps slipping further away.

Yet the omissions were even more grievous than the selections themselves. One of Pakistan’s pre-eminent white-ball batsmen, a craftsman, the only match-winner or a game-changer, scorer of four One Day International hundreds across 2023 and 2024, was treated not with the dignity befitting merit, but with the casual disdain of those whose interests were severed from the quest of excellence. He was neither summoned to Zimbabwe, nor entrusted in Australia, nor considered for South Africa, as though his feats with the bat existed in some alternate reality to which the selectors had chosen blindness.

The fate of Fakhar Zaman, a match-winner in the truest sense, was particularly symbolic, not just a cricketing casualty, but a philosophical one. Here was a player whose career witnessed the rarest fusion of audacity and impact, yet he was cast aside, not for failure, but for the sin of inconveniencing the egos of those ensconced in their administrative offices. Fakhar was not excluded for his inadequacies, but to be taught a lesson, a grotesque inversion of what selection ought to embody.

And as fate so often aligns itself with the indifferent cruelty of flawed process, the consequence was painfully inevitable. Saim Ayub, the youthful harbinger of possibility, the slender bridge between Pakistan’s muddled present and its elusive future, fell to injury, fracturing his ankle and leaving the edifice even more fragile than before. It was not just misfortune, but a philosophical collapse, the inevitable unraveling of a system that sees talent not as a resource to be nurtured, but as a commodity to be controlled.

In that collapse, Pakistan did not only lose a player; it stood exposed, a cricketing nation whose selections no longer served the game, but the self-preservation of those whose hands shaped it. Then there was Babar Azam, a cricketer who, for a fleeting moment, seemed to outdo the chaos around him. In a system that thrived on disorder, he was a rare constant, a batter who rose from the fragments not because of the system, but in defiance of it. He was the kind of player who made you believe, briefly, that maybe talent alone could still be enough. His cover drive, as much a signature as a nation’s collective sigh of relief, belonged to cricket’s eternal archive, a reminder that in this land of impermanence, beauty could still be permanent.

But beauty, especially here, is rarely left untouched. Form, once effortless, became a daily negotiation with doubt. Those silken starts, once preludes to masterpieces, began collapsing under the weight of expectation and the dissonance that lives within all Pakistani cricketers, the sense that you are only ever one inning away from the selectors forgetting your name.

And then came the strangest intervention. Babar Azam, the second-most prolific number three in the world, was told to abandon the one thing he had made his own, his place. A player conditioned to arrive with the game half-formed was told to open, to redefine himself at a stage where the innings were still shapeless. It was a decision both stunning and entirely ordinary in Pakistan cricket, a team that has long mistaken chaos for flexibility, and improvisation for strategy.

Babar, already trapped in his battle with form, was now forced to fight another: the battle against his own identity. A player who had, for so long, been the answer, now became the question. And somewhere in that forced mutation, something was lost, not just runs, but the assurance that, at number three, Babar Azam was the closest thing this team had to certainty.

What was it, then? A tactical adjustment? A desperate gamble? Or simply the latest example of a team, and a system, unable to resist the urge to fix what wasn’t broken, until it finally was. Did the selectors, one wonders, ever pause long enough to look into the intricate mosaic of Babar Azam’s ODI innings, not as a series of scores, but as a story unwrapping across a career?

Did they see the gentle arcs of accumulation, the crescendos of his cover drives, the spaces where hesitation crept in, and the innings that receded when certainty deserted him? Or did they, as is tradition, treat a player not as a work in progress but as a problem to be solved, a number to be moved, a solution to a question they didn’t fully understand?

Babar’s break-up by position was not just data; it was evidence of a batsman’s natural habitat, a rare alignment between talent, temperament, and place. To displace that was not just a tactical adjustment, it was a disruption of cricket’s most delicate ecosystem, a tampering with fate itself.

|

Babar Azam |

Position |

Innings |

Average |

Centuries |

|

|

No. 3 |

65 |

60.17 |

19 |

|

|

No. 4 |

20 |

42.20 |

03 |

|

|

Opener |

10 |

31.00 |

0 |

This would show a downward trend, a classic case of the ‘square peg, round hole’ syndrome that has defined Pakistan’s handling of celebrate players. One wonders if the selectors ever paused to study the inobtrusive truths of Babar Azam’s craft, the unhurried accumulation, the gentle tug between control and flair, the way he made number three his home, his sanctuary.

Instead, they seemed to view him not as a batsman in need of recalibration, but as a piece to be shifted on a board, a convenient solution to a different, unrelated crisis. There was no interrogation of what had truly dimmed his brilliance, no effort to restore his rhythm. They looked past the vast evidence of his mastery at number three, choosing instead to displace him into unfamiliar air, a batsman already at odds with himself, now tasked with reinvention for reasons that owed more to political expediency than cricketing sense. In doing so, they forgot that even the most terrific talent can fray when it is repeatedly untethered from the conditions in which it thrives.

|

Player |

Innings @ No. 3 |

Average |

|

Zaheer Abbas |

27 |

51.50 |

|

Inzamam Ul Haq |

57 |

46.70 |

|

Mohammad Yousuf |

55 |

53.10 |

|

Younis Khan |

104 |

51.26 |

|

Babar Azam |

65 |

60.17 |

It would have been simple. A chart, a data point, a clear, blinking sign, all pointing to Babar Azam’s extraordinary dominion over the No.3 position. That alone should have closed the case. But this is Pakistan cricket, where clarity is rarely the point, and logic is too linear a quest for the caprices of selectors and administrators addicted to reinvention. Instead of nurturing his natural habitat, the measured rhythms of No.3, where greats like Ricky Ponting, Rahul Dravid, and Virat Kohli constructed their legacies, dragged him to the top, handing him the harshest air of all.

Babar didn’t need displacement; he needed stewardship. The kind of careful career tending Pakistan’s system has historically found alien, a deliberate blueprint rather than the haphazard improvisation that so often defines the country’s cricketing existence. His career orientation should have been obvious:

A permanent No.3 anchor role, a place where his artistry could breathe, unbothered by the immediate panic of new ball survival, a sanctuary to build epics rather than scramble for bursts. And the perceptions that his role is of a match-winner like Virat Kohli, should be negated. His types are the innings builders, the impact batsmen, not the ones taking it deep and towards the end. Such batsmen are the consolidators, the pivots around them the others rally around.

A defined leadership plan, free from the theatrical reversals and conditional backing, where either the captaincy was his to own, even through form slumps, or it wasn’t — and his only task was to bat. A technical support team, curated for his needs, a coach who could polish his fluency, a data analyst decoding his mid-innings slowdowns, and a mental conditioning guide to shield him from the relentless din outside.

A measured T20 presence, limited to marquee events, so the white-ball burnout that has claimed so many before him does not turn into a predictable postscript. And, above all, workload management, the rarest and most valuable gift Pakistan cricket can offer a player it so often idolizes but rarely protects, the gift of longevity, of balance, of knowing when to pause before the inevitable collapse.

Babar Azam is not the first prodigy to be handled with the same blend of reverence and carelessness. But perhaps, if the system can learn, he could yet be the last. India’s handling of Virat Kohli is often cited as a case study in modern player management, a balance of talent cultivation, clear role definition, and a stable environment.

Kohli was groomed at No.3 in ODIs after his initial bursts as an opener in 2008-2009. By 2011, he was already the long-term No.3. India did not shuffle Kohli’s batting position needlessly, trusting him at No.3 across formats, allowing him to grow into it without mid-career experiments. Even in Tests, after initial middle-order slots, they anchored him at No.4 (Rahul Dravid’s old home), allowing him to own the role.

Kohli’s rise to captaincy was incremental and structured. In Babar’s case, he wasn’t ready, and it came as a surprise since Sarfraz Ahmad, the most deserving man out there was sacked because of a political outcome. He was unprepared to be handed over the responsibility and needed to mature in his place before being elevated to the leadership role.

Virat was eased in as vice-captain under Mahendra Singh Dhoni for years, learning leadership while focusing on batting. When Dhoni stepped away, Kohli took over in phases, Test captain first, then limited overs, with clear succession plans. Kohli had access to personal trainers, sports scientists, mental conditioning experts, and data analysts, allowing him to evolve his game. Fitness programs were tailored to his aggressive style, ensuring his body could sustain three-format cricket. India reduced Kohli’s T20I appearances post-2021, allowing him to focus on Tests and ODIs. Rotational rests were embedded into India’s calendar for all-format players, ensuring peak performance in key tournaments.

Babar’s shifts (No.3 to opener, captaincy handovers, selection pressures) have been abrupt, often crisis-driven rather than planned. Where India gave Kohli a team-first but player-aware pathway, Babar is often treated as both savior and scapegoat, expected to rescue the team while being repositioned at will. Babar fits into this lineage, a world-class batter being asked to cover for a flawed system, rather than the system being reformed to maximize his strengths.

I wonder, if the selectors just tried focussing on Babar’s career, the surges, the plateau, and how the numbers had reduced, slithering to mediocrity. What it required was chaperoning and not displacing him from the position of his strength.

|

Year |

Format |

Innings |

Runs |

Average |

Primary Batting Position |

|

2015 |

ODI |

4 |

122 |

30.50 |

No. 5 |

|

2016 |

ODI |

16 |

656 |

46.80 |

No. 3 |

|

2017 |

ODI |

18 |

872 |

67.10 |

No. 3 |

|

2018 |

ODI |

18 |

509 |

36.35 |

No. 3 |

|

2019 |

ODI |

20 |

1092 |

60.67 |

No.3 |

|

2020 |

ODI |

3 |

221 |

110.50 |

No.3 |

|

2021 |

ODI |

6 |

405 |

81.0 |

No.3 |

|

2022 |

ODI |

9 |

679 |

84.88 |

No. 3 |

|

2023 |

ODI |

21 |

892 |

47.0 |

No.3/ (opener (few matches) |

|

2024 |

ODI |

10 |

374 |

37.40 |

Opener/No. 3 (rotating) |

Then there was another ominous selection of Usman Khan, primarily an opener or a top-order batsman and a reserve wicketkeeper. He was tried in T20 Internationals after some blistering show in the Pakistan Super League. Nonetheless, he was seemingly exposed at the international level, unable to sync in the more competitive world with his technique and his batting fitness was brittle. Why was he chosen ahead of better choices already available, even an injury to Haseeb Ullah warranted Rohail Nazir to be handpicked. Usman’s credentials were dubious, at least not up to the international standards, and as a backup wicketkeeper whose ODI experience is precisely nil. To describe this as imbalance would be generous; it is not so much imbalance as the systematic defiance of logic itself, a conscious rejection of balance in favor of arbitrary selections driven by familiarity, personal allegiance, and laughably transparent agendas.

The exclusion of Aamer Jamal, a genuine all-rounder with both the skill and spirit required for modern white-ball cricket, in favor of the perpetually underwhelming Faheem Ashraf, is less a selection decision and more a manifesto of mediocrity. Aamer Jamal, by any objective measure, represents the future: seam movement, resolute batting, a temperament forged not in the tepid cauldron of domestic irrelevance but in the fire of high-pressure matches. And evidently, he was within the scope having been chosen to tour Zimbabwe, Australia, and South Africa. Faheem, on the other hand, is the totem of Pakistani selectors’ pathological attachment to failed familiarity, a player whose mediocrity is both chronic and predictable, and whose repeated selection is less about performance and more about maintaining the fragile equilibrium of Pakistan’s dysfunctional dressing room or national politics.

Yet it is not just the individuals selected that betray the intellectual hollowness of the process, it is the absence of any coherent vision. No discernible philosophy binds these names together, no stylistic or strategic intent informs their inclusion. They are not the products of a system, nor the reflections of a tactical ideology; they are disparate names thrown together by a committee too paralyzed by politics and too bereft of competence to sculpt a side fit for modern cricket.

Dr. Nauman Niaz is the Sports Editor at JournalismPakistan.com. He is a civil award winner (Tamagha-i-Imtiaz) in Sports Broadcasting and Journalism and a regular cricket correspondent, covering 54 tours and three ICC World Cups. He has written over 3500 articles, authored 14 books, and is the official historian of Pakistan cricket (Fluctuating Fortunes IV Volumes – 2005). His signature show, Game On Hai, has received the highest ratings and acclaim.

March 15, 2025: Explore the dynamic relationship between athletes and sports journalists, examining the challenges, ethical dilemmas, and mutual benefits that shape the sports media landscape.

March 08, 2025: An in-depth analysis of Pakistan cricket's descent into chaos under Aaqib Javed's leadership, examining the controversial selection decisions, political interference, and systemic failures that undermined the national team ahead of the ICC Champions Trophy 2025.

March 02, 2025: An unsparing analysis of Pakistan's Champions Trophy 2025 squad selection reveals not merely inexperience but a systemic rot of patronage networks, political expedience, and intellectual bankruptcy within Pakistan's cricket governance, continuing a tragic history of selection failures.

February 28, 2025: An in-depth analysis of Pakistan cricket's selection dysfunction ahead of the ICC Champions Trophy 2025, examines how the absence of a philosophical framework has led to incoherent squad choices, conflicting decisions, and a system that prioritizes survival over strategy.

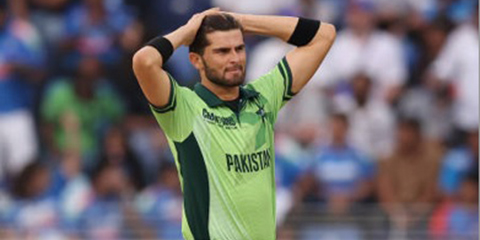

February 26, 2025: Shaheen Shah Afridi’s rise was a spectacle of raw, untamed talent. But Pakistan’s cricketing establishment failed him, leading to a career plagued by injuries and mismanagement. Can he reclaim his dominance, or is his best past him? Read the full story.

February 26, 2025: Explore the extraordinary legacy of Major Dhyan Chand, India's hockey wizard who redefined the sport, won three Olympic golds, and inspired generations with his unmatched brilliance.

February 24, 2025: An incisive analysis of Pakistan cricket's systemic failures, examining how bureaucratic inertia, self-serving former players and resistance to modernization have eroded the nation's cricketing excellence despite abundant talent.

February 21, 2025: Delve into the complex challenges facing Pakistan cricket as it grapples with outdated systems, political interference, and resistance to modernization. Dr. Nauman Niaz reveals how the transition from passion-driven success to bureaucratic inefficiency has left Pakistan's cricket legacy hanging in the balance.

April 11, 2025 Sindhi journalist AD Shar was brutally murdered in Khairpur, Sindh. His body was found dumped on Handiyari Link Road. PFUJ has declared a three-day mourning period and demanded justice.

April 10, 2025 The Azad Jammu and Kashmir government has filed a case against The Daily Jammu & Kashmir and its staff for alleged fake news, drawing condemnation from PFUJ and IFJ, who demand immediate withdrawal of the FIR and an end to media repression in Pakistan.

April 08, 2025 Journalist Arzoo Kazmi alleges that Pakistan's state agencies, including the FIA, have blocked her CNIC, passport, and bank account while threatening her. She calls it a direct attack on journalism.

April 07, 2025 The Islamabad High Court has directed IG Islamabad to produce journalist Ahmad Noorani’s missing brothers, as the Ministry of Defence denies custody. SIM activity was traced in Bahawalpur, and investigations into their suspected abduction continue.

April 07, 2025 Journalist and Raftar founder Farhan Mallick has been granted bail by a Karachi court in a case concerning anti-state content aired on his YouTube channel. He still faces separate charges related to an alleged illegal call center and data theft.